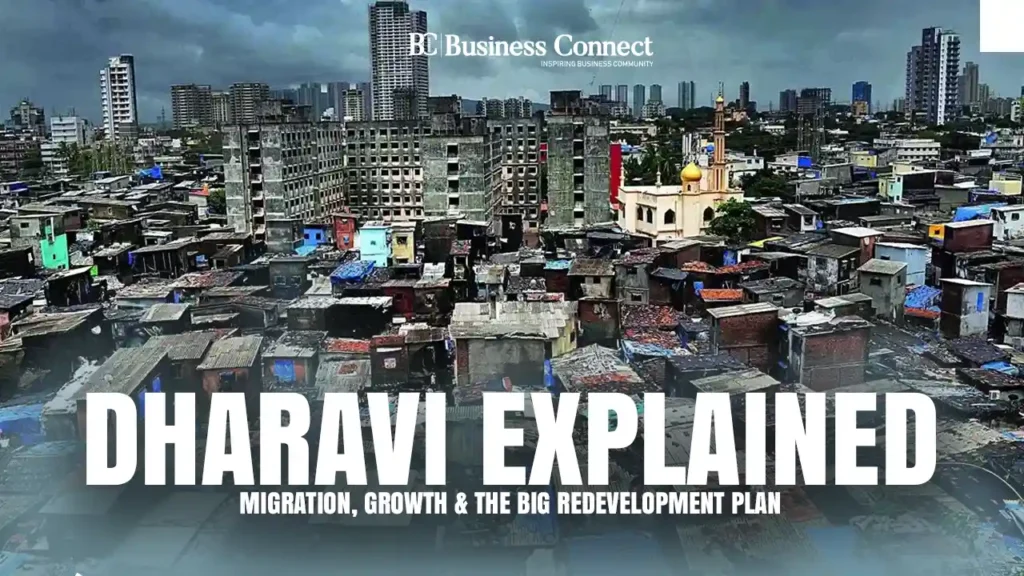

2.1 square kilometers of area, home to over 1 million people, and a population density of nearly 500,000 per square kilometer. These staggering figures belong to Dharavi—Asia’s largest slum, with an annual economy worth more than a billion dollars.

Dharavi Slum Migration Story | What the New Redevelopment Project Promises

Located right in the heart of Mumbai, Dharavi is not just a settlement, it’s a treasure trove of stories. Stories of survival, resilience, and ambition. Like that of a don who survived 19 bullets, a craftsman who arrived empty-handed but built a fortune from scrap, or a father who shaved his son’s head during the 1992 riots to keep him safe. Thousands of such tales are woven into the lanes of Dharavi.

The story of Dharavi begins in a swamp, shaped by decades of struggle, migration, and transformation. And today, as it stands on the brink of being turned into a ₹3 lakh crore redevelopment project, understanding Dharavi’s real story becomes more important than ever.

Hello, I am Anurag Tiwari. You are reading Business Connect Magazine, where today we explore how Dharavi became Asia’s largest slum.

How Did Dharavi Become a Slum?

How Did Dharavi Come Into Existence? To understand how Dharavi came into being, we need to travel back in time. The city we now know as Mumbai was once a cluster of seven separate islands, separated by shallow creeks and swamps. These islands were named Little Colaba, Colaba (meaning the land of the Koli fishing community), Worli, Mazgaon, Parel (also known as Paradi), Mahim, and the Isle of Bombay.

Until the 17th century, these islands were under Portuguese control. But history took a turn when Portuguese princess Catherine of Braganza married King Charles II of England. As part of her dowry, the Portuguese handed over Bombay (as it was then known) to the British. The islands were largely used for fishing, so the British Crown leased them to the East India Company for £10 a year to facilitate trade.

However, being separate islands created major logistical and communication challenges. People had to travel repeatedly by boat, and the swampy land between the islands made life difficult. To solve this, the East India Company started land reclamation projects to connect the islands.

In 1708, a causeway was built between Mahim and Sion—a raised road constructed over water. Near this causeway, a settlement began to take shape, which came to be known as Dharavi. The name has two possible meanings: “the edge of a creek” or “loose soil.” Initially, Dharavi was a swampy stretch with mangrove forests. The Koli fisherfolk were the first to settle here, establishing a small hamlet called Koliwada, which still exists in Dharavi today.

By the 19th century, Dharavi began to grow in size and population. In 1864, the Bombay Municipal Corporation officially brought this area under city limits. As Bombay developed into a major port and trade hub in the early 20th century, industries that generated waste and pollution were pushed out of the main city—and Dharavi, being on the outskirts at the time, became the natural relocation ground.

In 1887, a tannery opened in nearby Sion, and soon Dharavi became the center of leather production. Tamil-speaking artisans from Tamil Nadu, many from marginalized communities, migrated here to work in the leather industry. They established one of Dharavi’s oldest neighborhoods.

But leather wasn’t the only trade. In the 1930s, a large group of potters from Gujarat arrived in Bombay. Skilled in making earthenware, they were granted 99-year land leases in Dharavi in 1895 by the British. They settled in an area that became known as Kumbharwada (the potters’ colony)—a neighborhood that remains one of Dharavi’s most iconic settlements even today.

Dharavi: Crowded Streets, Endless Stories

Dharavi is one of the most densely populated places on Earth. As mentioned earlier, it has one of the world’s highest population densities. The reason so many people ended up here was simple: work and land. Even if all one could afford was a shack, it was still a place to call home. Compared to the rest of Mumbai, land in Dharavi was far cheaper, and so migrants kept settling here.

In the early 20th century, Tamil leather workers arrived. Then came Gujarati potters. Later, artisans from Uttar Pradesh brought their embroidery and tailoring skills, which gave birth to Dharavi’s booming ready-made garment industry.

Then came 1947—Independence and Partition. Along with freedom came pain. Millions were displaced. While most refugees fled to Delhi, many also came to Mumbai, and some of them found shelter in Dharavi. What was once a settlement of just a few thousand grew to around 3,000 residents. Between 1941 and 1951, Bombay’s population shot up from 1.5 million to 2.3 million. This wasn’t just Partition—it was also because poor families from across India came looking for work. Gujarat sent migrants, Maharashtra’s villages sent migrants—Dharavi absorbed them all.

By the time India became independent, Dharavi had already become Bombay’s—and perhaps India’s—largest slum. But the migration never stopped.

In the 1960s and 70s, disaster struck rural Maharashtra. Drought in the Western Ghats, floods elsewhere, and widespread crop failure forced entire villages into starvation. People had no choice but to leave their land. It is said that during this time, one out of every three or four migrants from rural Maharashtra ended up in Mumbai. Many of them, like Mahadev Kadam’s father—a leather worker from Pune district—settled in Dharavi.

He had lost his farm to drought and was encouraged by friends already working in small leather workshops in Dharavi to move here. His story was not unique. Thousands of farmers, laborers, and artisans from Maharashtra, Bihar, and Uttar Pradesh poured into Mumbai, and Dharavi became their address of survival.

They built huts wherever space allowed—along railway tracks, on swampy sewage land, under tin, bamboo, or plastic sheets. The settlement grew without any planning or design—just endless clusters of shacks. Dharavi kept expanding, its face kept changing, and with it came thousands of personal stories.

Writers like Joseph Campana (author of Dharavi: The City Within) have captured these stories. For instance, Saeed Khan, a belt-buckle polisher who came from Jamshedpur in 1979 with no money and no roof over his head, slept on footpaths. Starting with polishing buckles, he eventually designed his own. One of his three-piece buckle designs became so famous that people started asking, “Is this a Saeed Chikna buckle?” From a street-side worker, he turned into a millionaire.

Another story is that of Hanumanti, widowed at 18, who came to Mumbai with nothing. She started a small plastic recycling business with just ₹200. Life seemed to improve until a fire in 2007 destroyed everything—her stock, her hut, even her dogs. No leader, no businessman, no landlord helped her. She pawned her jewelry and rebuilt her business. Today, her daughter Lakshmi works with her. Hanumanti says: “In Dharavi, for a woman to run a business, she needs courage—courage to work hard, and courage to fight off troublemakers.”

But Dharavi is not just about survival—it also has a dark underworld. Author Hussain Zaidi has written about DK Rao, a don who once controlled parts of Dharavi. Rao, originally Ravi Mallesh Bora from Gulbarga, Karnataka, came from a poor laborer’s family belonging to a denotified tribe labeled as “criminal” by the British. He began as a petty thief, then graduated to armed robberies.

In jail, he came into contact with Chhota Rajan’s gang, and soon became one of its key men. His criminal record grew, from bank robberies to extortion rackets in Dharavi’s redevelopment projects. By the late 1990s, he was running Rajan’s operations in India.

Perhaps his most shocking story is from November 11, 1998, when Mumbai police ambushed him and his gang during a gang war between Rajan and Dawood Ibrahim. Rao claims he was shot 19 times but survived by playing dead under the corpses of his associates. At the morgue, he suddenly stood up and shouted, “I’m alive!” That survival made him a legend in Mumbai’s underworld. Later, he turned to spirituality, practicing yoga and meditation even while continuing to exert influence from jail.

Dharavi: From Underworld Wars to Billion-Dollar Redevelopment

As years passed, Chhota Rajan’s most trusted lieutenants began to fall one by one. His man known as Mat Bhai—often called the “Director of India Operations” for Rajan—was killed in a police encounter in 2000. After his death, Rajan’s gang began to fragment.

Rajan tried to rebuild, forming a dozen-odd replacements, but they too were wiped out. Between 2000 and 2011, 11 gang members were killed in encounters. In the end, only one loyalist survived—DK Rao.

In Mumbai’s underworld, it’s often said Rao endured because of his fierce loyalty. He once even planned to go to Dubai to assassinate Dawood Ibrahim to avenge Rajan. He shared loot generously with his men, posted their bail when needed, and even learned to maneuver the legal system while in jail. That’s why former Mumbai ATS chief Rakesh Maria nicknamed him “Black Mamba”—the deadly snake that doesn’t let go of its prey until it dies.

Maria once said: “He’s no ordinary man. He’s a survivor. For Rajan, Rao is what Chhota Shakeel is for Dawood.”

Even today, in 2025, Rao remains active, recently arrested again in an extortion case. His shadow still looms over Dharavi.

But Dharavi’s history is not only about the underworld. It carries wounds far deeper—none greater than the riots of December 1992 and January 1993.

On December 6, 1992, the Babri Masjid was demolished in Ayodhya. The fires of communal hatred spread across India, and Dharavi too was engulfed. Sixty-two people were killed—43 Muslims and 17 Hindus. Temples, mosques, madrasas were destroyed. Shops and homes were burned. Dharavi’s main streets—especially 90 Feet Road and the leather market—were devastated.

That leather market, once a bustling hub with Muslim-owned warehouses on one side and Hindu-run tanning workshops on the other, was reduced to ashes. Communities that had lived together for generations were suddenly divided. Tamil Hindus and Muslims who once shared neighborhoods parted ways. Hindu families left; Muslim clusters became dominant. Dharavi was scarred—socially, politically, and emotionally.

The riots reshaped politics too. The Shiv Sena gained influence in certain parts of Dharavi, especially among Dalit leather workers. Yet amid the rubble, efforts at reconciliation emerged. In his book Dharavi: The City Within, Joseph Campana recalls one symbolic moment: a poster created to promote unity.

Originally, it was supposed to feature cricket captain Mohammad Azharuddin and others, but when news of his personal scandals broke, plans changed. Instead, four local children—Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, Christian—were photographed together. For the Hindu role, a child had to shave his head and wear a rudraksha necklace. Many families refused, fearing stigma. Finally, a Muslim leader shaved his own son’s head. The poster became iconic, plastered across Dharavi, buses, shops, even police stations—a fragile but powerful message of unity.

Still, the scar of 1992–93 never fully healed.

Life Inside Dharavi

For outsiders, Dharavi may appear like chaos—a labyrinth of shanties. But to live here is to experience some of the harshest living conditions on earth.

Mumbai’s average population density: 24,000 people per sq km (already among the world’s highest).

Dharavi’s average: 100,000 per sq km.

Some pockets: up to 300,000 per sq km—making it one of the densest human settlements in the world.

The lanes are so narrow that two people cannot walk side by side. Sunlight barely reaches the ground. Homes are often just 10×10 feet single rooms, where families of five or more live, eat, sleep, and sometimes even work.

Author Marie Carolyn, in her book Dharavi: From Mega Slum to Urban Paradigm, describes living with the Kadam family in 1994–95. Their 10×10 home was divided across two floors. Downstairs doubled as a living room and bedroom. Upstairs, a dark, airless room without a window held seven children who slept pressed together, managing only 3–4 hours of restless sleep amid noise, mosquitoes, cockroaches, suffocating heat, and the toxic smoke of burning garbage.

Infrastructure is dire:

Open drains overflow during monsoons.

Water shortages force women and children to stand in line for hours.

Toilets are scarce—on average, one per 500 people. Many resort to open defecation in drains or even the nearby Mithi River.

Diseases like cholera, diphtheria, typhoid, and TB are rampant. Doctors here report thousands of cases monthly. Life expectancy is below 60 years, compared to India’s average of 67.

Dharavi: A Slum and a Factory

Yet Dharavi is not only a slum—it’s also an economic powerhouse. It houses about 5,000 businesses and 15,000 small workshops. Most are home-based: the house is the workshop, and the workshop is the house.

Leather: Once supplying boots for the British army, Dharavi still exports leather goods. Its homegrown brand “90 Feet” is known for quality.

Pottery: Generations of Gujarati potters in Kumbharwada produce millions of clay lamps for Diwali every year.

Garments: Migrants from Uttar Pradesh built Dharavi’s ready-made garment trade, stitching and embroidering clothes for markets across India and abroad.

Recycling: Dharavi is known as India’s “Recycling Capital.” Roughly 60% of Mumbai’s plastic waste is processed here. Metal, paper, glass, e-waste—all are sorted, cleaned, and resold. This recycling industry alone is worth over $1 billion annually and employs 250,000 people.

In short, Dharavi is a giant informal factory that never sleeps.

Redevelopment: Promise or Betrayal?

Today, Dharavi sits on 600 acres of prime land in the very heart of Mumbai—next to the gleaming Bandra-Kurla Complex. For decades, developers and governments have eyed this “golden land.”

Efforts began in the 1980s, but projects failed. In 2004, the Dharavi Redevelopment Project (DRP) was launched, but politics, debt, and protests stalled it. Finally, in November 2022, the Adani Group won the bid with an investment of ₹569 crore.

A joint venture—Navi Bharat Mega Developers Pvt. Ltd. (NMDPL)—was formed with the Maharashtra government. The plan:

Redevelop 300 acres of Dharavi for housing.

Construct 24 crore sq ft of buildings in total.

10 crore sq ft for rehabilitation of Dharavi residents.

14 crore sq ft for commercial sale.

Estimated project value: ₹3 lakh crore ($36 billion).

Timeline: 7 years for housing, 17 years for completion.

Architect: Hafeez Contractor.

Each “eligible” resident—defined as someone who settled in Dharavi before the year 2000—will receive a 350 sq ft apartment. Those who came between 2000–2011 will be shifted to rental homes outside Dharavi. Post-2011 settlers get nothing.

This eligibility cut-off has sparked protests. Many fear losing not just their homes but also their livelihoods. Dharavi is both residence and workplace; will the new apartments provide workshop space? Or will Dharavi’s economy be uprooted for the sake of shiny towers?

Critics say the project benefits builders more than residents. Supporters argue it will finally bring dignity, hygiene, and proper housing to millions. Political battles rage—Rahul Gandhi and Uddhav Thackeray accuse the government of “selling Dharavi to Adani,” while leaders like Eknath Shinde and Devendra Fadnavis insist it’s for the people’s welfare.

Stories of broken promises fuel skepticism. In 1994, Santosh Nakar signed a deal with a developer for a flat, but after a decade of delays, he attempted self-immolation in protest. Others, like Abbas from Kumbharwada, felt deceived by NGOs collecting data under false pretenses to aid redevelopment.

The truth is, Dharavi’s redevelopment is not just about real estate. It’s about identity, survival, and community. Will Dharavi’s soul survive modernization? Or will it vanish under glass towers and malls?

That answer lies in the future.

Dharavi: Asia’s Largest Slum – FAQ

1. Where is Dharavi located?

Dharavi is in the heart of Mumbai, India, spread across 2.1 square kilometers.

2. How many people live in Dharavi?

Over 1 million residents live here, making it one of the most densely populated areas in the world. In some pockets, the density reaches 300,000 people per sq km.

3. How did Dharavi come into existence?

Dharavi began in the 1700s as a swampy settlement near the Mahim–Sion causeway. Initially inhabited by the Koli fishing community, it grew rapidly during British colonial rule as industries like leather tanning and pottery were pushed out of central Bombay. Migrants from Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, Uttar Pradesh, and Maharashtra kept arriving, turning it into a hub of labor and survival.

4. Why did Dharavi become a slum?

Because of unchecked migration, lack of urban planning, and poverty. Migrants built huts wherever space was available—on swampy land, near railways, or on garbage dumps. Dharavi expanded without sanitation or infrastructure, becoming Mumbai’s largest slum.

5. What are the main industries in Dharavi?

Despite its conditions, Dharavi is a thriving informal economy worth over $1 billion annually. Key industries include:

Leather exports (brand “90 Feet” originated here).

Pottery in Kumbharwada.

Garments and embroidery from Uttar Pradesh migrants.

Recycling, processing nearly 60% of Mumbai’s plastic waste.

6. What are living conditions like in Dharavi?

Families of 5–7 often live in 10×10 feet rooms.

On average, there’s 1 toilet for 500 people.

Water shortages and open drains are common.

Diseases like TB, cholera, and typhoid are widespread.

Life expectancy is below 60 years.

7. Has Dharavi been affected by communal violence?

Yes. During the 1992–93 riots after the Babri Masjid demolition, 62 people were killed in Dharavi. The violence destroyed temples, mosques, and businesses, and reshaped the social fabric—splitting once-united Hindu and Muslim communities.

8. Are there underworld connections in Dharavi?

Yes. Dharavi has been linked to Mumbai’s underworld. Figures like DK Rao—a close associate of Chhota Rajan—ran extortion rackets tied to redevelopment projects. Rao famously survived being shot 19 times in 1998.

9. What is the Dharavi Redevelopment Project?

The Dharavi Redevelopment Project (DRP) is a ₹3 lakh crore ($36 billion) plan led by the Adani Group and the Maharashtra government.

300 acres to be redeveloped.

24 crore sq ft of construction planned.

10 crore sq ft reserved for resident rehabilitation.

Each “eligible” resident (settled before 2000) to get a 350 sq ft flat.

Timeline: 7 years for housing, 17 years overall.

10. Why is redevelopment controversial?

Only pre-2000 residents qualify for free housing.

Many fear losing not just homes but also workshops and livelihoods.

Critics say builders gain more than residents.

Supporters argue redevelopment will bring better housing, sanitation, and dignity.

11. What makes Dharavi unique?

Dharavi is more than a slum—it’s a self-sustaining city within a city. It’s a place of hardship, but also of resilience, innovation, and entrepreneurship. From millionaires rising out of scrap recycling to families surviving droughts, Dharavi is a symbol of both India’s struggles and its fighting spirit.

12. What is the Dharavi Redevelopment Project (DRP)?

A ₹3 lakh crore project by Adani Group + Maharashtra Govt.

Goal: transform Dharavi into modern residential & commercial spaces.

Timeline: 7 years for rehab housing, 17 years overall.

Promise: every “eligible” resident gets a 350 sq ft flat free.

13. Why is redevelopment controversial?

Only pre-2000 residents qualify.

Businesses/workshops may lose space.

Fear of cultural & social displacement.

Critics say: “Builders gain, poor lose.”

Supporters say: “Better housing, sanitation, dignity.”

14. How do Dharavi residents feel about redevelopment?

Mixed reactions:

Some welcome modern flats & clean water.

Others fear losing livelihood & community bonds.

Many demand workshops + homes, not just housing.

15. What makes Dharavi unique?

World’s most productive slum.

Economy larger than some small nations.

A blend of poverty, entrepreneurship, and survival.

Symbol of India’s resilience—where hope thrives even in harshest conditions.

15. What are the main cultural aspects of Dharavi?

Ganesh Chaturthi, Eid, Diwali are celebrated together.

Street food: vada pav, idlis, biryani.

Local art: Warli paintings, pottery, leather craft.

Hip-hop & rap culture growing (many Dharavi rappers are famous).

16. How is Dharavi shown in global media?

Negative side: overcrowding, dirt, poverty.

Positive side: innovation, small industries, resilience.

Example: Slumdog Millionaire showed both faces.

17. What is the Dharavi Redevelopment Project?

₹3 lakh crore project led by Adani Group & Maharashtra Govt.

Aim: Build 1 lakh flats for residents, modern towers, malls, offices.

Rehab homes: 350 sq ft free flat for eligible families.

18. Why is redevelopment controversial?

Only residents living before 2000 get free housing.

Workshops & factories may lose space.

Fears of gentrification – locals may be pushed out, builders profit more.

19. What are Dharavi’s biggest challenges today?

Sanitation & clean water.

Healthcare access.

Education & employment for youth.

Balancing redevelopment with preserving livelihoods.

20. What makes Dharavi unique in India?

It’s both a slum & a billion-dollar economy.

A place where poverty and entrepreneurship co-exist.

Dharavi shows how India’s urban poor survive, adapt, and innovate.