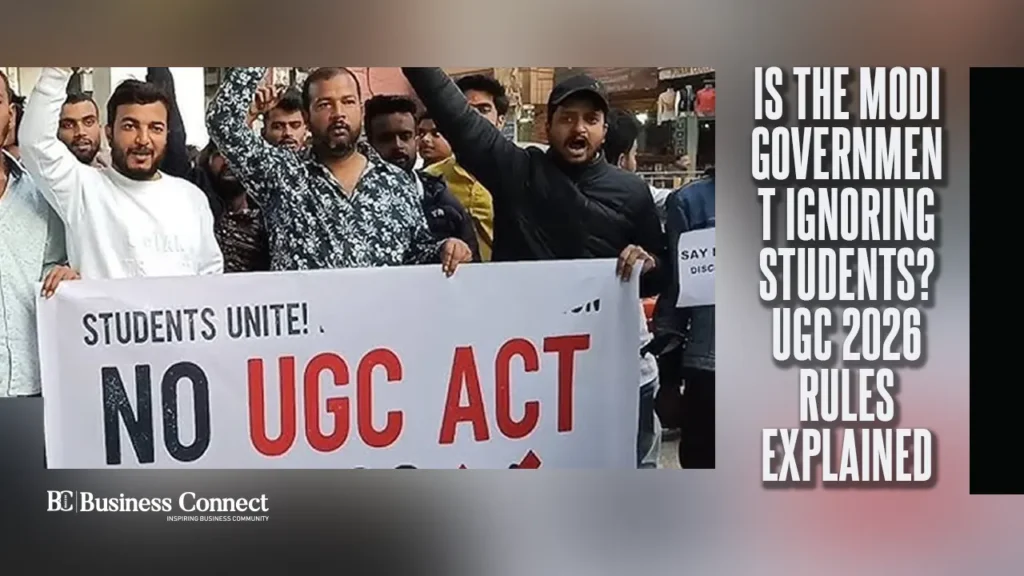

UGC 2026 Rules Under Fire: Students Question Govt’s Education Reforms

Will education in India’s colleges and universities now be driven purely by merit and hard work, or will students be forced to study under constant fear of surveillance and complaints?

This question has become crucial today because the new UGC regulations introduced in January 2026 have triggered a debate that can no longer be ignored. Two contrasting narratives have emerged from this development.

On one side is the Modi government and the UGC’s vision, which claims these rules are aimed at making college and university campuses discrimination-free and safer for all students. Their argument is rooted in a harsh social reality: many victims hesitate to file complaints due to social pressure, fear, or stigma. According to the government, strict regulations are necessary to ensure that every student can pursue education with dignity, respect, and security.

However, on the other side is a section of society that feels deeply anxious about these very rules. They are raising uncomfortable questions—asking whether being from the so-called “savarna” community is now being treated as an offence in itself. Their concern is that a legal framework is being created in which they may be presumed guilty, with little or no opportunity to prove their innocence. To them, it feels as though a system meant to eliminate fear has instead created a new kind of fear.

That said, the existence of fear alone does not automatically prove that the regulations are wrong. What it does highlight, however, is the need for a serious discussion on whether these rules can be improved or made more balanced. The debate now centres on a critical concern: in the name of equality, is a system being created where identity itself becomes a disadvantage?

These questions are significant, and social media today is flooded with arguments, opinions, and accusations from all sides. But to truly understand this controversy, it is essential to first examine the UGC regulations themselves—what exactly they say, why they were introduced, and what problems they aim to address.

The UGC regulations were formally introduced on 13 January 2026. The government stated that these rules would be implemented under the framework of the New Education Policy, with the objective of ensuring equal opportunities for all students within educational institutions. In light of repeated reports of discrimination on campuses over the past few years, the government felt that the existing rules were inadequate. As a result, the Modi government made it mandatory for every college and university to establish dedicated centres and committees to address such complaints.

Under the new regulations, if a student believes they have been subjected to unfair or discriminatory treatment, they can file a complaint either online or through a helpline. The institution is then required to complete a full inquiry within 15 to 30 days. Overall, the government’s intent appears clear: to create a system where students from marginalized and backward communities do not feel unsafe or excluded within academic spaces.

However, it is this very focus on protecting disadvantaged students that has led to deep concern among students from the general category. The heart of the controversy lies in the changes introduced compared to the earlier framework. Under the 2012 regulations, there was a provision stating that if someone deliberately made a false allegation of discrimination, the complainant could also face punishment. This acted as a safeguard to prevent misuse of the law.

That safeguard has now been removed in the 2026 regulations, and this is where much of the fear stems from. Experts argue that the government may have taken this step to ensure that genuine victims are not discouraged from reporting incidents, as the fear of punishment can sometimes silence even those who are telling the truth. However, general category students worry that if a complainant faces no consequences even when a complaint is proven false, the law could potentially be misused as a weapon to harass or falsely implicate others.

This fear is amplified by the reality that whenever a law lacks strong checks and balances, the possibility of misuse always exists. As a result, many are asking an uncomfortable question: has belonging to the general category itself become a liability in today’s system?

Another controversial aspect of the new regulations is the deployment of Equity Squads. The government views these squads as protective teams that will monitor sensitive areas of campuses to ensure the safety of vulnerable students. According to the UGC, these squads will regularly patrol hostels, canteens, and common sitting areas, maintaining vigilance across the campus.

Among students, however, these squads are often perceived as a form of constant surveillance rather than protection. General category students fear that vague terms such as “indirect discrimination” could lead to normal, everyday behaviour being misinterpreted and reported as wrongdoing. This perception of being watched has further intensified anxiety and mistrust on campuses.

Imagine a classroom where a teacher hesitates ten times before correcting a student’s poor academic performance, fearing that even a genuine academic remark might later be interpreted as caste-based humiliation. Imagine students thinking twice before joking with one another, unsure whether casual interactions could be misread. Does this environment risk eroding the very freedom of learning—where students and teachers can speak openly, question freely, and grow through honest dialogue?

There is another deeper consequence of these regulations: institutional pressure. The UGC has made it explicitly clear that if a college fails to handle a complaint properly, it could face severe consequences—ranging from the suspension of funding to even the cancellation of its recognition. The inevitable question then is: what happens in practice?

To protect their funding, reputation, and positions, college principals and managements may feel compelled to take swift and harsh action, sometimes prioritising damage control over justice. When the credibility of an institution is at stake, administrations may choose to quickly settle cases or appease complainants rather than conduct a genuinely fair and balanced inquiry.

This is precisely where students from the general category feel most vulnerable. Their concern is that the rules clearly define where and how to file a complaint, but remain largely silent on how a student who has been falsely accused can prove their innocence. With strict deadlines imposed on colleges to resolve complaints, general category students fear that speed may be valued over fairness—raising a haunting question: will innocent students be repeatedly trapped in the process?

The law is often guided by the principle that it is better for a hundred guilty individuals to go free than for one innocent person to be punished. Yet the fear among general category students is that while empowering the vulnerable is necessary and morally right, doing so without adequate safeguards may unintentionally create a new imbalance. They ask whether, in attempting to eliminate one form of discrimination, another is quietly being allowed to grow. Is the fear of caste that once existed in one direction now spreading in another?

Supporters of this argument often point to conviction rates as a warning sign. Recent reports indicate that conviction rates under the SC/ST Act range between 34% and 42%. General category students repeatedly cite this to highlight that a significant number of cases fail in court due to lack of evidence or are resolved through compromise. This does not mean that all cases are false—but it does suggest that many cases collapse after causing irreversible damage.

Even in high-profile cases like Rohith Damle, by the time investigative reports concluded years later that no one was guilty, the careers, reputations, and mental well-being of the accused students or professors had already been destroyed. This leads to a painful and practical question: if a general category student is falsely accused today and proven innocent years later, who will compensate for the loss of time, dignity, career, and mental health?

The absence of a strong counter-mechanism only deepens this anxiety. When complainants know that even false allegations may not invite consequences, the fear is that complaints could multiply—not necessarily in pursuit of justice, but because the system allows it. This is what makes the issue so deeply complex.

There is also an undeniable political dimension to this debate. The general category voter base has historically been a strong pillar of support for the Modi government. Many within this group believed the government stood for merit and fairness. However, after the introduction of these regulations, doubts are beginning to surface. Some now wonder whether policy decisions are being shaped more by electoral calculations than by balanced governance.

The 10% EWS reservation was seen as an attempt to build trust, but that trust now appears fragile. General category students argue that when it comes to campus committees formed under these rules, neutrality is often missing, and their voices lack meaningful representation.

For any healthy society, it is essential that every group feels heard. When a student begins to feel that they are viewed only as an oppressor, their sense of belonging collapses. Over time, this psychological pressure takes a toll—and perhaps this is one of the reasons why today’s brightest and most capable students are increasingly thinking about leaving the country in search of fairness, dignity, and opportunity elsewhere.

The question now is clear: there may be many complaints, but what is the solution? How do we bring balance into the system?

To create harmony between equality and justice, criticism alone is not enough. What is needed are practical and constructive reforms—reforms that protect the interests of both general category and marginalized students. Only then can fear be removed from all sides.

The first suggestion is straightforward: no major punitive action should be taken without a preliminary inquiry. Before initiating strict measures, the administration must first examine whether a complaint has sufficient merit.

The second recommendation is the formation of an independent review panel on every campus—a body that includes external experts and retired judges who can investigate cases objectively, without institutional or political pressure, and arrive at the truth.

The third suggestion focuses on restructuring complaint committees. Each committee should include at least one genuinely neutral member—someone with no political affiliation and no ideological bias—who evaluates cases solely on facts and evidence.

Only when such safeguards are in place will the fear created by these regulations among one section of students begin to fade. Democracy, after all, is about inclusive progress—Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas. Creating fear in one group to eliminate fear in another is not true democracy. Equality does not mean intimidating one section of society; it means moving forward together.

Discrimination must be eliminated—there is no debate on that. Strong laws are essential because genuine victims deserve justice. But justice is meaningful only when it is equal for everyone. The UGC must introduce a balance in these regulations so that no innocent student is trapped unfairly.

The existence of fear does not prove that the rules are wrong—it proves that they need refinement. If we talk about ending discrimination on one side while pushing another group into constant anxiety, that is not justice—it is injustice.

The dream of a Developed India can be fulfilled only when every student is able to prove their merit without discrimination and without fear.

We hope these suggestions reach those who shape policy. We also encourage you to actively share this discussion so that the idea of balanced justice reaches a wider audience.

Before we sign off, a small request: do join our WhatsApp channel so our connection with you grows stronger and we can deliver our content directly to you—without delay. We will also continue to take your suggestions seriously and raise important issues with honesty and neutrality.

Finally, we want to hear from you.

Do you believe that removing fear from one group by creating fear in another is the right approach? Or do you feel these rules need correction?

Share your honest views in the comments—not based on surnames or identities, because justice is not decided by surnames. Just as we strive for fairness and balance, we hope you will do the same in your responses.

FAQs on UGC 2026 Regulations Controversy

1. What is the UGC 2026 Regulations controversy about?

The controversy revolves around new UGC regulations introduced in January 2026, aimed at making college and university campuses discrimination-free. While the government says the rules protect marginalized students, many from the general category fear misuse, excessive surveillance, and lack of safeguards for the falsely accused.

2. Why did the UGC introduce new rules in 2026?

The UGC introduced these rules under the New Education Policy after repeated reports of caste-based discrimination on campuses. The government believes older regulations were insufficient and that stricter mechanisms are necessary to ensure dignity, safety, and equal opportunity for all students.

3. How can students file complaints under the new UGC rules?

Students can file complaints through online portals or dedicated helplines. Colleges and universities are required to investigate and resolve complaints within 15 to 30 days.

4. What are Equity Squads, and why are they controversial?

Equity Squads are campus teams tasked with monitoring sensitive areas like hostels, canteens, and common spaces to protect vulnerable students. While the government sees them as a safety measure, many students perceive them as surveillance units that may restrict free interaction.

5. Why are general category students worried about these regulations?

General category students fear that:

The removal of punishment for false complaints may lead to misuse

There is no clear mechanism to prove innocence

Vague terms like “indirect discrimination” could criminalize normal behaviour

Colleges under funding pressure may act unfairly to quickly close cases

6. What changed from the 2012 UGC regulations?

The 2012 rules included a safeguard allowing punishment for false or malicious complaints. This provision has been removed in the 2026 regulations, which critics say weakens checks and balances.

7. Does fear of misuse mean the rules are wrong?

Not necessarily. The fear highlights the need for better balance and refinement, not the complete rejection of the rules. Strong laws are essential to protect genuine victims, but safeguards are equally important to prevent injustice.

8. How does institutional pressure affect justice on campuses?

The UGC has warned colleges that improper handling of complaints could lead to loss of funding or recognition. This may push administrations to prioritise reputation and speed over fairness, potentially harming innocent students.

9. What role does conviction data play in this debate?

Critics often cite SC/ST Act conviction rates (around 34–42%) to argue that many cases fail due to lack of evidence. While this does not imply cases are false, it raises concerns about reputational damage caused before legal closure.

10. Are there political concerns linked to the UGC rules?

Yes. Many general category voters—traditionally a strong support base of the Modi government—feel alienated. Some believe policy decisions are being driven by electoral pressures rather than balanced governance.

11. What solutions have been suggested to bring balance?

Key suggestions include:

Mandatory preliminary inquiry before major action

Independent review panels with external experts and retired judges

Inclusion of neutral members in complaint committees

These measures aim to protect both genuine victims and innocent students.

12. Can equality exist without fear?

True equality cannot be built by replacing one group’s fear with another’s. Justice must be fair, transparent, and equal for all, ensuring protection without intimidation.

13. How does this issue impact India’s future?

A climate of fear—real or perceived—can push talented students to seek education abroad. A Developed India is possible only when students can learn, compete, and succeed without discrimination and without fear.

14. What is the core question this debate raises?

The central question is whether removing fear for one group by creating fear in another aligns with democratic values—or whether the UGC regulations need recalibration to ensure balanced justice.